OG: Where I'm Comin' From

How I approach this stuff, etc

Dear Readers-

I’m writing this slowly, because I suspect you’re all fast readers, and reading this might actually add a few seconds to your projected lifespan. It’s the New Math, and yea: it’s a conspiracy!

No, but seriously: I just now realized that, I “finished” writing my last post, the 4th (of 23) theses on History, then I sent it out, realizing I can edit later. So, I sent it out to all my subscribers (all 42 of you wonderful folks), thinking later tonight or tomorrow or sometime next week, when you decided to have a look, you’d get the edited version. I guess I subscribe to my own Substack? I must, ‘cuz I got it…and it looked embarrassing. When I clicked on it, the 17 or 23 or 42 edits I made (I am the Paganini of committing typos) didn’t show up. So: in the future, I will hold off sending anything out until I’ve gone over it a few times after letting it cool off.

Why did I rush getting it out? Maybe vanity. Maybe I actually thought I caught some hot ideas and wanted everyone else to share in it. Maybe I have ordinary delusions of being a “good writer.” Maybe I felt like I had been a bit of a laggard.

I will not be using AI (I promise!)

Consider I’ve taken an oath.

I think AI shows promise for making extremely fast calculations based on big data sets, and that its primary value will be to scientists and technologists. Beyond that, my ideas about it — and I read A LOT about it — drops way off. I’m simply not impressed. Indeed, I’m alarmed by the versions of it that are already acting psychopathic. I’m alarmed by the quality of character of the people hyping it. That humans are already having psychotic breakdowns with their reactions to their - gawd help us - “relationship” with “their” AI bot. That the people behind AI seems like the worst wealthy class history has thrown up at us, and we’ve seen some pretty monstrous assholes so far, haven’t we?

My main reason for not using AI is: I’m olde-fashioned and wanna do a stupid-assed thing like: use my own nervous system and dead-tree books to think with. I’m committed to Team Carbon over Team Silicon. A few months ago I read a major AI tech cultist (sorry: I know it’s ad hominem, but it’s all I got), Blaise Agüera y Arcas argue that AI models “lack bodies, life stories, kinship (or) long-term attachments,” but this was “irrelevant” when we consider questions like “capability, like those about intelligence and understanding.” (I’m drawing from THIS article.)

What’s wrong with this view? It assumes a Humans are Machines POV, and Machines are Humans. It assumes knowledge is Third Person, a god’s eye-view, that leaves humans experiencing the world out of the equation. Which is literally mindless. But humans are self-organized biological systems. The atoms in your cells won’t be the same ones in a few days. We are enacting our own consciousness, while your AI will always be a silicon-based machine that has no consciousness. This is a strong stand, I know. Prove me wrong.

Anyway: when you read me you’re getting that same old thing those of you 40 or over were used to, as you grew up: some homo sap who’s writing something based on his experience, and who is surrounded by dead-tree books.

WARNING: I will use the Internet to fact-check, mostly ‘cuz I have an olde dude fallible memory. BUT: I will not use AI to fact-check. More like Wikipedia. (I love Wikipedia!) But probably more often than most people: other books will be used for fact-checking. The idea that I fact-check at all should getcha a little hopped-up in this world of breezy, brazen bullshit (and asinine, atrocious alliteration?), to toot my own horns.

(Aye: horns. Plural. I must get to a specialist in Zurich, to quote an old humorist.)

On “Overweening”

First dictionary definition for overweening: “Showing excessive confidence or pride.” I’ll leave it to you, Dear Reader, to ascertain if I’m being ironic there or not.

On “Generalist”

Around age 19 - technically, during the Carter Administration - I read some ideas around people who Knew Way More Than I’d Ever Comprehend. Some of these people were “intellectuals,” while others were “scientists,” and still others, “philosophers.” To paraphrase Dr. Seuss — or someone like ‘at — O! The Things I Don’t Know!

I began to read books by people who seemed to know. And I continue to do so, and the oddest phenomenon about all that, to me, is this: the more I read and understood ideas…the more I realized I hardly knew anything. And that trend has continued. Part of the reason, I suggest to myself, is that I had a faulty idea of the overall space of what there was to know in the first place. Friggin’ place is huge. Way bigger than the Astrodome.

(photo by Robert Banach)

But along the way - probably mid-20s - I realized some Knowers were people who knew a lot about all kinds of things. They talked or wrote learnedly about astrophysics, then went off about the history of medicine without a hitch. They could start in on Sanskrit, which would somehow morph into Jung’s aspects of the Self, swerve into the lane: psychotropic drugs in prehistory, then end on Industrial Era politics in Europe. The romance of knowledge and ideas. Some of these people were polymaths, others merely bookish, some savants, a lot of ‘em generally: Generalists. (To be juxtaposed with Specialists.)

The problem with being a Generalist is you’re too damned interested in everything and you need to draw some lines somewhere. Approaching my dotage (or already well into it; I can’t tell because that’s an area in which I lie to myself quite a lot: define “dotage”!), I guess I was never all that in to: Malaysian history, some of the minor geologic eras, the intricacies of the feudal system, pop music 2010-now, or gauchos. Among many other topics. Why do I say this? ‘Cuz I remain a damned eejit about those topics to this day. Things could change…

For personal biologically-based reasons that are complicated (maybe I’ll get to it in some other OG article), I never did specialize in something. Which is where the Do-Re-Mi moolah, the ca$h, the wads of semolians, the legal tender, the…you get the picture, brothers and sisters, uhh…is. Belatedly, I realized the Generalist ought to Specialize in something that pays really well, while pursuing their Generalist whims and paths in their off-hours. I Specialized in rock guitar: hardly a smart roll of the dice, money-wise. Your odds of obtaining a fat mortgage and paying for utilities and the essentials by being a rock guitarist are only a tad shorter than your odds of winning the Powerball. (That has something to do with the lottery, right?)

Brief history of my autodidacticism

I’d taken a lot of college classes and changed my major from Music to English to Psychology to Humanities. I dropped formal school mostly due to a sleeping disorder that interfered with work and my musical pursuits. I consider most of my education as autodidactic, meaning I had a fool as a teacher. (We autodidacts are required to drop that line into something we write at least once, as per United Autodidact-Generalists Union #420-69 agreement 23, 1973, April Fool’s Day. Get it? Fools! Yea, they thought they could seize the world back then…great little bunch.)

A nano-version of my reading life: in elementary school I literally read every biography of sports heroes in the school library. From age 8 or 9 until age 25, I was an assiduous reader of the Los Angeles Times, because my mom subscribed. I basically read everything but Business and Classifieds. The LAT was actually pretty much what you could legit hope for, given LA’s history, with the Chandlers, et.al. As a kid, I had no idea: I just consumed it every day, like, as McLuhan said of the daily newspaper reader: mentally, into a warm bath. A very long feature story began on Page 1, left hand column, then went on to multiple pages. Hot newspaper reportage, at times sizzling. Yes, in Los Angeles.

There were books hanging around the house, mostly ‘cuz mom thought they were good to have. A couple of atlases; Grimm’s Fairy Tales; Your Erroneous Zones, by Wayne Dyer, who I later learned was just sorta cribbing from Albert Ellis. A weird book that I might have on my shelves somewhere today: Faith, Love and Seaweed, about natural living, natural foods, and health. Definitely my mom’s choice. I had a couple of How and Why Wonder Books, the sorta thing they actually sold in the supermarket in the 1970s. In 7th grade a friend had Man, Myth and Magic in his bedroom, which had me swooning and I didn’t understand why at the time. In my teens I read a lot of Sports Illustrated, High Times, Creem, and Rolling Stone. Later I became a pretty hardcore enthusiast for Scientific American. I avoided what was assigned in junior high and high school and read anything the public library had about music, including music theory, which I taught myself and thought other musicians did, too. I also read anything that had to do with what used to be called the “counterculture.” By age 16 or so, I got the idea that there were some books and authors that were horrible, evil, very bad, déclassée, notorious, disreputable, pornographic, not-reviewed in respectable periodicals, scandalous, obscure, etc: those were the books I gravitated toward. In a lot of ways, this hasn’t changed.

In my 30s I began to read the history of science, modernist literature, and the deep history of what I had conceptualized as a counterculture that went back to 1300 BCE or so. At one point I rented a room from a miserable old man who had a complete set of Adler and Hutchins’s Great Books. They were furniture to him; I don’t think he had ever opened more than one volume. I offered him $100 for the set, and he said yes. I distinctly remember carrying that set upstairs to my room and piling them on the floor, as I had no shelves. I sat on the floor endlessly perusing what was in them - roughly a “canon” of Western Lit from Homer to Freud - and learning how to use the Syntopicon, which must have had an influence on my idiosyncratic indexing of ideas. I still haven’t read Apollonius of Perga’s On Conic Sections, but Herodotus, Montaigne, Lucretius, Plutarch, Melville, Darwin, Rabelais, Swift, and William James’s endlessly trippy 1890 textbook Principles of Psychology have provided endless delights.

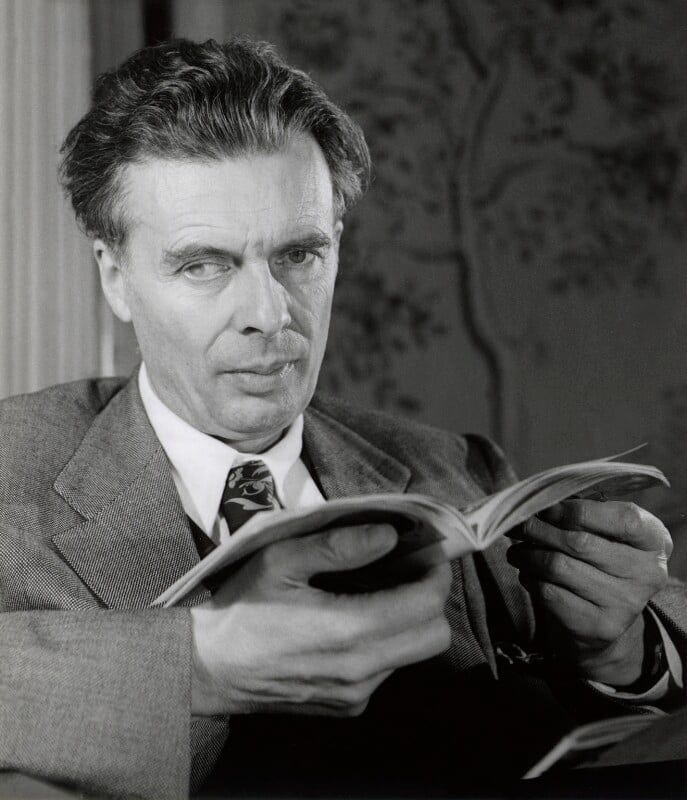

(Aldous, basically blind and yet a terrific art critic who got his nose so close to a canvas it almost touched the painting.)

Many of you know me as a reader of Robert Anton Wilson, and these spaces will continue to hit on all things RAW and RAW-adjacent. It’s what you signed on for.

Before I discovered RAW, my RAW was Aldous Huxley, another great Generalist. I was not flagged at all in tracking down Aldous’s work and reading it, over and over. Imagine living in a family like the Huxleys! My mother had never been to college and gave up reading serious literature in her 20s; my father had taken some classes at Pasadena City College, but he was borderline anti-intellectual. He had had some amazing professor teach Don Quixote, but it kinda ended with that. I realized my entire childhood was filled with people who were either anti-intellectual or ignorance-is-blissfully unaware of that culture. Where did I get…all this Generalist-mania? I’m still not sure, and why should you care? It’s not interesting.

(A typical moment, remembered: a bandmate showed up early for rehearsal, and I had just awoke from my cubbyhole in the very room where we practiced. I had some books stashed there. Bass player: You…read? Me: Yea… Bass player: Why?)

Sometime in my 30s, I read a bunch of essays by Gore Vidal, still a pretty big influence on me although I disagree with a lot of his opinions (EX: Pynchon is a novelist for university professors: a very bad take), but one essay really lit a fire: on Thomas Love Peacock and the Novel of Ideas. I realized that I read novels not only to be transported by the worlds created and the beauty of prose found therein, but I had been taught to recognize ideas wherever there was writing, including the labels of soup cans and billboards. Dr. L. David Sundstrand is to blame, bless him. No doubt McLuhan also influenced me in this way.

OG Finds RAW

Finding prodigious Generalist Robert Anton Wilson was one of the happiest accidents of my life. I had never heard of him, but while browsing a book shop in Torrance, CA, after my wife and I ate at our favorite greasy spoon, I saw Right Where You Are Sitting Now on the shelf, and wondered what the hell it could be. It looked really interesting. No only his ideas, but the form of the book. I bought it, read it all night, went to work bleary-eyed, then read it again as soon as I was caught up on sleep. I quickly became obsessive and found and bought almost all of his books to date. He was like Aldous: a novelist who also published a lot of non-fiction, plays, etc. Perhaps more than anything, he made Ontology and Epistemology endlessly fascinating for me. I would say he derives Ontology from Epistemology. He influenced me to read deeply in Korzybski, Crowley, and Wilhelm Reich, three writers I’d only heard of before then. He had been friends with Philip K. Dick, and I had gone through a Dickhead phase myself years earlier. He made me try to understand the non-understandable: quantum theory, zen, Daoism, phenomenological sociology, and logical paradoxes. RAW addressed ideas that were not “polite”, were shunned by academia (psychedelic drugs, the occult, conspiracy theories, alternative economic ideas, sex magick, etc), and “marginalized,” to use Chomsky’s term. I’ve described RAW’s oeuvre as a step-up transformer. At least for myself: that’s how he functioned.

I think in retrospect that Wilson’s working class background, his freelance situation for much of his writing life, and his lifelong-retained Brooklyn accent also endeared me to him. (I’ve spent almost my entire life in California, but I love American accents that don’t sound like everyone I grew up around.) I was not really “aware” of this the first couple of years after I found him and read him very closely, but over the years I became aware of my need for the “working class intellectual” voice. And no doubt because I came from a lower-middle class broken home: alcoholics, mental illnesses, absentee father, etc. I loved to read absurdly well-read people but they were usually academics, extraterrestrial-like polymaths, or well-ensconced in Manhattan and its myopias. I had read Eric Hoffer and thought, there are people like this. RAW was, for me, the real deal along this line. Aye, David Graeber more recently and gawd damn what a loss! Give us more working class intellectuals!

Some Methods of Study I’ve Used

Open-ness to ideas: I’ve been heavily influenced by an academic book I’ve worn out and which has given me a minor psychedelic buzz ever since I first read it and it continues to do that for me: The Social Construction of Reality: A Treatise in the Sociology of Knowledge, by Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann (1966) Both of them studied under Alfred Schutz, who imported his teacher Edmund Husserl’s phenomenology into sociology, and it feels like that’s where it needed to be, but I digress. In a golden passage early in the book, B&L discuss the sociology of knowledge as it had existed prior to themselves, and they note that they were going to do something their forebears had not: include anything taken as “knowledge” in a given culture. I remember reading that for the first time and just walking around for the next week or so, my head buzzing with the idea. It has always stuck with me: even if I personally think an area of human thought is dubious, silly, or just plain wrong or BS, there are fellow humans for which it is meaningful, and so I ought to take those ideas seriously while I study them.

I remember there was an immediate application: I went to party and some people were talking seriously about Astrology, which I normally would have debunked. You know: that kind of jerk at a party. Tryna show how smart he is but he’s just a big ol’ drag. But B&L were ricocheting around my brain-pan, and had already had a heavy influence on me and I asked questions and learned a lot about how this field lent meaning to their lives. I now see my debunking self in horror. (In Berger’s memoir, Adventures of An Accidental Sociologist: How To Explain the World Without Becoming A Bore, he tells an anecdote about a couple of sketchy characters who showed up at his office, IIRC, at Boston U. They knew Berger was one of two guys who had written an influential book with the title The Social Construction of Reality, and when they got down to brass tacks, they wanted Berger to just tell them how to construct reality, because they had…political ideas. He was forced to explain to them it, uhh, doesn’t work like that.)

(When it comes to ideas aligned with culture-wide cruelty and that favorite primate activity: “punching downward”, I have a slightly less agnostic stance and will indeed debunk. I could be on acid and if you said, “cutting taxes on the rich is good for everybody because they reinvest and it all trickles down to everyone,” I could wax the floor with your argument. Next! My gawd what a stupid fucking idea.)

The only other academic-based book that has had a similar effect on me as B&L’s is Metaphors We Live By, by George Lakoff and Mark Johnson. I was never the same after that one. To this day, there are people who think conceptual metaphor theory is trivial, and I can’t tell if they’re wrong (horribly so), or if I fell for something that spoke to some foundational bug in my own thinking. I use conceptual metaphor all the time and it helps me make sense of so many things I don’t think I could jettison it even if some epochal paper was published that “proved” it was a wrong idea.

(Along these lines: Korzybski was pretty cranky and repetitive, but the value I’ve derived from Science and Sanity seems incalculable at this point for me. He’s persona non grata in academia, but I don’t care, being a perennial outsider/gnostic anyway. See Outsider Theory: Intellectual Histories of Unorthodox Ideas, Jonathan Eburne, 2018: he doesn’t mention Korzybski, but he does address a lot of fringe ideas that I’ve found attractive, and he’s really interesting about them.)

I’ve written in a journal/diary/log every day since September 1989. It’s compulsory, boring to read, and I don’t care. You would keel over from boredom reading that crap. But: it has activated those circuits for writing and if I decide to write something, it’s not a chore to get going. Writing well seems like another question entirely. And obviously: I give it a shot. (Is it obvious? To put it in E-Prime: Boy does my face seem red.)

I used to buy cheapie 8x11 lined notebooks and keep notes there, linking ideas together by drawing arrows all over the place. It got unwieldy. That’s when my index card mania hit: I found little black boxes for 3x5 lined index cards, which I crammed with headings and notes. (I quickly found 4x6s were much better.) The most interesting aspect of this, to me to this day, was deciding what was a Topic worth making a heading for. After reading Robert Anton Wilson: does Guerrilla Ontology deserve its own topic? How is that idea different from Discordianism, or what I eventually called “Erisiana”? How do these ideas overlap or diverge from Model Agnosticism? Often the answer is to pick one, then at the end of a note that, say, comes from reading a book by Paul Krassner, it goes into Erisiana, but I append “see guerrilla ontology.” I already have 12 4x6s crammed with notes, front and back, under Information Theory: how is that different from my notes on John Von Neumann and Norbert Wiener? Only my conscious practice of mental categorization knows the answer to that. Bateson has his own cards, and so does Lilly.

This system takes up very little space, is extremely handy and easy to use, and it’s idiosyncratic in that when you decide some lines in a poetry book belong under subject headings for Mathematics, or Satire. It’s the way YOU group ideas, so there’s creativity involved. Just make sure to write legibly. Many’s the time I’m doing some research and I can’t read WTF that word is, my cramped handwriting sucks, maybe I was drunk? and it’s been so long I can’t guess. Make your notes speak to your way of thinking. (A tad late for me but better late than never: see Sönke Ahrens’s How To Take Smart Notes. This autodidact says thanx! )

Sometimes I’m going through old index cards and I don’t remember reading this book listed under Deconstruction, much less the title or author. I must have read that, though: there it is: pp.318-319: has interesting disagreement with Derrida over books already deconstructing themselves on the shelf, right now. Musta been good. Did I find it in Los Angeles’s public library? Berkeley’s? Sonoma County’s? Check those catalogs: ah: the book’s not listed in any of those places. Possibly an Interlibrary Loan, or it’s been weeded (a sad thought) out of whatever library I found it in. I certainly don’t own it. Oh, well…

Not one copy of Thomas Hatsis’s LSD: The Wonder Child is available (it was available, got lost and now San Francisco Public is re-ordering one copy as of the moment I write this), but there are around 400 copies available of John Grisham’s The Exchange: After The Firm (2023). And so it goes. I predict: the lone copy incoming of Hatsis will disappear from the shelves within a year. “Missing” is all it will say in the catalog. Or there will be an entry, but under holdings it will say, “No copies available.” How passive! I get why books on UFOs, conspiracy theories, psychedelic drugs and Taylor Swift, “walk” as some librarians say, but when one copy of an academic book on James Joyce, The Varieties of Joycean Experience, was supposedly on a shelf, it quickly walked, early in the pandemic. I’m now in the weeds, talkin’ outta school, but the same thing with the one copy of James Laughlin, New Directions and the Remaking of Ezra Pound ,by Greg Barnhisel. When it came out, I was stoked. Then it walked. No copies available, anywhere. Who steals books on Pound and Joyce? Not me. I consider that some species of Evil. Why? ‘Cuz I like to assume I have some godforsaken doppelganger out there who’d want to read that weirdo shit, too. I want him to be happy, and my intuition tells me he wants me all doped-up on scads of choice books, too.

You’re wondering: hey OG: why don’t you index your ideas on some spread sheet on your computer? Short answer: I love the manipulability and tactility of index cards, printing with a pen, thumbing through an actual card file and pulling a batch of them out on, say, Tantra. But hey: you do you! And have a blast! I’m extremely Olde Skool.

I love owning books but I’m not a book collector. The latter, to me, cares about first editions. I only want what they call “reading copies” in the book trade. I will buy the cheapest copy used online, even if it’s loudly stamped “WITHDRAWN from Benedict Arnold Junior College, Catskillia, New York.” I have around 3200 books in the house now. Which is kinda embarrassing: they take up so much space! They’re really the only things I “want.” And I rarely buy a book anymore: lack of space, cost, my pending death, etc.

Few things make my heart fill with gladness like a wall crammed with books. I have to double-shelve a lot of ‘em due to space. It’s a sort of fetish to accumulate books and arrange them in your own idiosyncrasies. I often think of Prospero’s line, “My library was dukedom large enough.” It feeds the little Walter Mitty in me.

One of the great joys, and this has happened to me many times: I forgot I had a copy of some book, but as I got up close to a shelf, there it is. I take it down, blow off some dust, and utter inwardly, hello my little friend. Then I’ll start reading this thing, and it’s a blast. One of many examples, I was thinking about Burroughs and his use of gangster and underworld con artist patois, and how SJ Perelman also made hilarious use of that lingo, and I knew David W. Maurer’s The Big Con covered some of this, ‘cuz I had checked it out from the library. But apparently, I had also found it for cheap, came home and stuck it on a shelf with other gangsters and forgot about it. Same thing happened with Arthur Quinn’s Figures of Speech, a little book about rhetoric by an ex-Berkeley professor. I kept seeing recommended by people who enjoy Rhetoric, and wished I had it. I had forgotten it was one of about 30 books I inherited from my father-in-law when he died. Has this ever happened to you? It’s like finding a $20 in the couch cushions, right?

And there are a great many books I not only know exist and may have actually read once before, but they are out of print, or lost by the library systems I have access to, and few things are more frustrating in my little privileged, sheltered life. (Not counting the kakistocracy’s tentacles, as of this date.) EX: why is there not one copy of Prophets, Cults and Madness by Stevens and Price in the 111 libraries in California and Nevada that I have access to via the Link+ system? I read that book years ago and want to read it again. I’d like my own copy, but lemme see what a used copy is going for…$39.99. For me, skint: yikes. Many years ago, I checked out Schrodinger’s Cat and the Golden Bough, by Randy Bancroft. I was enthralled. I’d like to read it again. Aaaand…scour the local libraries: not in any library system I have access to. Not anymore. Used copy: $86.08. Sigh…Ezra Pound railed about books going OP and thought it some sorta conspiracy by “beaneries” (academics) and publishers, but I see it as just: I was one of the last of the Weird Ones who loved that book, it sat on the shelves, then got “deaccessioned,” a librarian’s term for: we need more room for computer terminals. The Board hath spoken.

(Currently MIA from my own shelves: Ron Rosenbaum’s wonderful book.)

Having books: when you move, they are the bane of your existence. But all mine spark joy, so no Marie Kondo-ing me, ok? I organize them by Dewey (I worked in public libraries for ten years) and a personal system of “these kinds of books belong with these other kinds.” I rarely have more than a few moments before finding something, although right now I have no idea WTF I did with my copy of Ron Rosenbaum’s delightful The Secret Parts of Fortune. I know I own that muthah; I just don’t know why I didn’t shelve it with my conspiracy theories or my stuff on Angleton…There have been times I went looking for a book I knew I owned, but couldn’t find it. And it was conspicuously facing me the whole time, it’s just so in my field of vision so often I couldn’t see it until I focused on reading every shelf; I erred in remembering the spine as black: I call this my own Purloined Letter Effect. It’s a mild hazard.

Why do I do all this? I’d like to give an original, if not witty answer, but in all honesty, I’ll just paraphrase Dr. Samuel Johnson, who wrote the first English dictionary (supposedly). Under Lexicographer he gave as part of his definition: “a harmless drudge.” (Also: I’m weird and besides, it’s fun!)

Just wanted to drop a note to say, I am so very glad you are writing this newsletter and I’m excited to read more. Thanks!

Thank you for writing this post!

“the oddest phenomenon about all that, to me, is this: the more I read and understood ideas…the more I realized I hardly knew anything.”

The idea of knowledge being, if not actually infinite, so vast that it seems to us to be virtually infinite brings Borges to my mind. After reading you, I felt compelled to re-read a couple of his stories, the Library of Babel and then Tlön, Uqbar and Orbis Tertius (I found it amusing that this last one would contain a line on “gauchos”, one of the few topics on which you claim to still remain a damned eejit).

To me, there is something of the Generalist, or at least of the scholar of the esoteric, that is usually implied in Borges’ fictions and style. Puzzles, labyrinths, forgotten knowledge and dusty books…

The vertigo-inducing glimpses of infinity that Borges gives his readers, could that be part of what drives the incessant, obsessive-compulsive, and decidedly vain pursuit of always more arcane knowledge in the Generalist? I’m thinking here less of a dopamine fix than a mystical quest for cosmic understanding… The Godhead as Information, maybe?

In another comment, I saw a bout on the 8C model. I like the idea of correlating upper and lower circuits, so I usually have the metaprogrammer as C7 because I see it as a natural follow-up to the semantic C3. Borges and his writings in the shape of an MC Escher drawing remind me of Douglas Hofstadter and the trappings of a mind stuck in the paradoxes of logic. I also find a sense of dread in Borges perhaps akin to the Generalist’s existential intuition that a lifetime won’t be enough to know all there is to know…

Perhaps the Generalist is trying to be all of the Five Blind Men of the Sufi parable at once. But in so doing, maybe confusion arose and SHe failed to realize that SHe’s now gropping at the other blindmen rather than the elephant. Meaning, gropping hirself? Seems like a Strange Loop, but those tend to arise within the Metaprogrammer and, again like Bob Wilson said, in the end it’s all brain circuitry that we’re looking at…